Doughnut Economics

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist by Kate Raworth

🚀 The Book in 3 Sentences

Traditional economics and ways of thinking don’t cover the wider need in our society today.

Doughnut economics proposes a radical, visual new model of thinking about economics in the 21st century.

🎨 Impressions

The author has pushed their old textbooks aside and sought out emerging ideas, exploring new economic thinking with open-minded university students, progressive business leaders, innovative academics and cutting-edge practitioners. This book brings together the key insights discovered along the way, that should be part of every economist’s toolkit today.

How I Discovered It

I have heard a fair amount about the book, and it seems to fit into its own category of books. I am interested in a new model of economics and this book seemed to match that interest.

Who Should Read It?

If you studying economics this book will provide a new take requiring you to challenge existing preconceptions in traditional texts. If you are interested in a book that combines both social policy, environment needs and economics this book does this.

✍️ My Top 3 Quotes

As the ingenious twentieth-century inventor Buckminster Fuller once said, ‘You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.

In the twentieth century, economics lost the desire to articulate its goals: in their absence, the economic nest got hijacked by the cuckoo goal of GDP growth.

Students must learn how to discard old ideas, how and when to replace them … how to learn, unlearn, and relearn

📒 Summary + Notes

A New Visual Model:

The most powerful tool in economics is not money, nor even algebra. It is a pencil. Because with a pencil you can redraw the world.

You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.

This book takes up this challenge, setting out seven mind-shifting ways in which we can all learn to think like twenty-first-century economists.

By revealing the old ideas that have entrapped us and replacing them with new ones to inspire us, it proposes a new economic story that is told in pictures as much as in words. What if we started economics not with its long-established theories, but with humanity’s long-term goals, and then sought out the economic thinking that would enable us to achieve them?

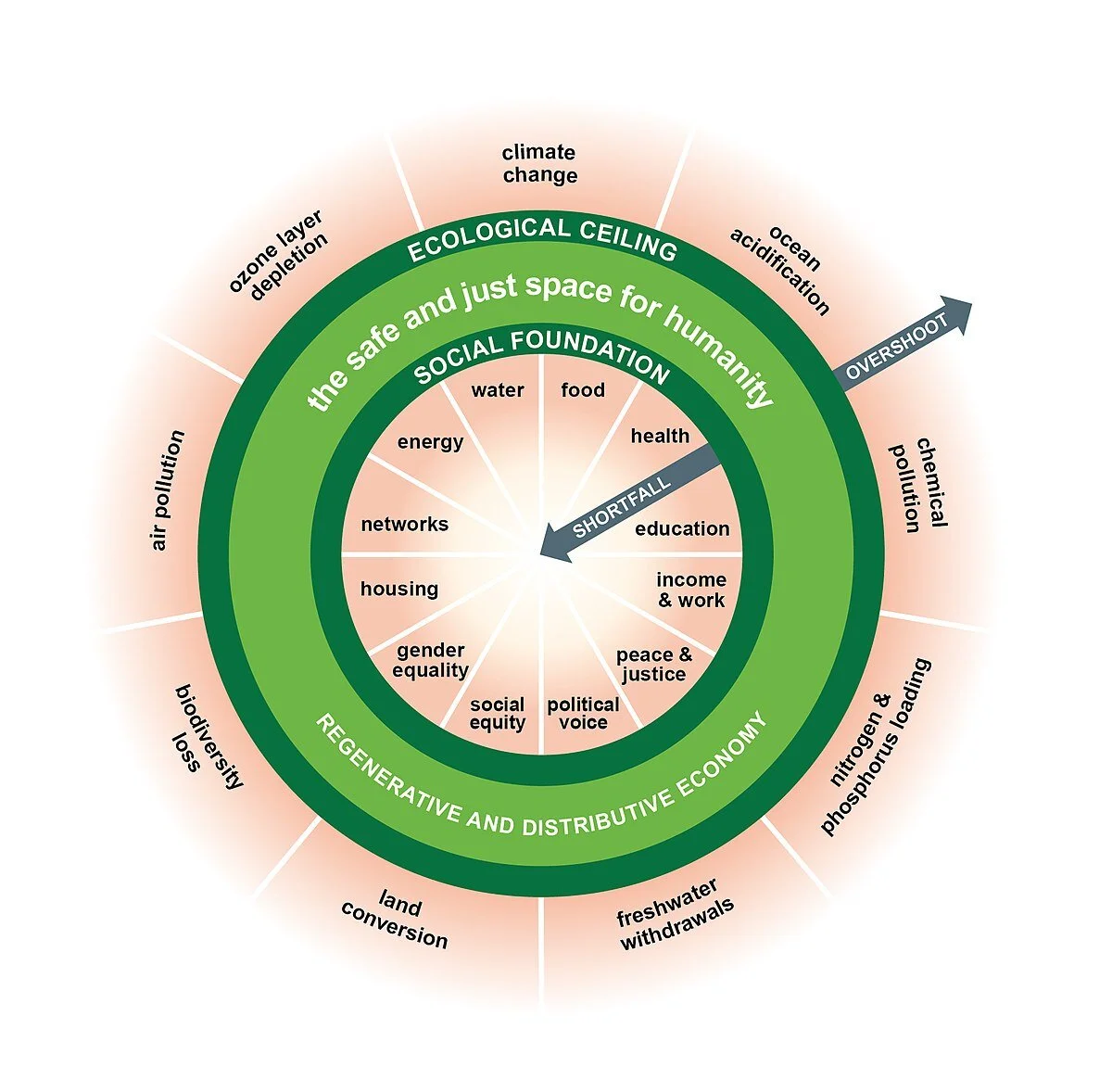

The essence of the Doughnut: a social foundation of well-being that no one should fall below, and an ecological ceiling of planetary pressure that we should not go beyond. Between the two lies a safe and just space for all.

Changing The GDP Goal

For over 70 years economics has been fixated on GDP, or national output, as its primary measure of progress. That fixation has been used to justify extreme inequalities of income and wealth coupled with unprecedented destruction of the living world. For the twenty-first century a far bigger goal is needed: meeting the human rights of every person within the means of our life-giving planet. And that goal is encapsulated in the concept of the Doughnut. The challenge now is to create economies – local to global – that help to bring all of humanity into the Doughnut’s safe and just space. Instead of pursuing ever-increasing GDP, it is time to discover how to thrive in balance.

Measured as the market value of goods and services produced within a nation’s borders in a year, GDP (Gross Domestic Product) has long been used as the leading indicator of economic health. But in the context of today’s social and ecological crises, how can this single, narrow metric still command such international attention?

Though claiming to be value-free, conventional economic theory cannot escape the fact that value is embedded at its heart: it is wrapped up with the idea of utility, which is defined as a person’s satisfaction or happiness gained from consuming a particular bundle of goods. but not once did we seriously stop to ask whether GDP growth was always needed, always desirable or, indeed, always possible.

Soon growth was portrayed as a panacea for many social, economic and political ailments: as a cure for public debt and trade imbalances, a key to national security, a means to defuse class struggle, and a route to tackling poverty without facing the politically charged issue of redistribution.

It deepened, as governments, corporations and financial markets alike increasingly came to expect, demand and depend upon continual GDP growth – an addiction that lasts to this day, orientational metaphors such as ‘good is up’ and ‘good is forward’ are deeply embedded in Western culture, shaping the way we think and speak.

An Open System

So let’s restore sense from the outset and recognise that, far from being a closed, circular loop, the economy is an open system with constant inflows and outflows of matter and energy.

The economy depends upon Earth as a source – extracting finite resources like oil, clay, cobalt and copper, and harvesting renewable ones like timber, crops, fish and fresh water. The economy likewise depends upon Earth as a sink for its wastes – such as greenhouse gas emissions, fertiliser run-off, and throwaway plastics.

Earth itself, however, is a closed system because almost no matter leaves or arrives on this planet: energy from the sun may flow through it, but materials can only cycle within it. That is why the market’s power must be wisely embedded within public regulations, and within the wider economy, in order to define and delimit its terrain. It is also why, whenever I hear someone praising the ‘free market’, I beg them to take me there, because I’ve never seen it at work in any country that I have visited.

Institutional economists have long pointed out that markets (and hence their prices) are strongly shaped by a society’s context of laws, institutions, regulations, policies and culture. A market looks free only because we so unconditionally accept its underlying restrictions that we fail to see them.

Simply putting aside the Circular Flow diagram and drawing the Embedded Economy instead transforms the starting point of economic analysis. It ends the myth of the self-contained, self-sustaining market, replacing it with provisioning by the household, market, commons and state – all embedded within and dependent upon society, which in turn is embedded within the living world. It shifts our attention from merely tracking the flow of income to understanding the many distinct sources of wealth – natural, social, human, physical and financial – on which our well-being depends.

This new vision prompts new questions. Instead of immediately focusing on making markets work more efficiently, we can start by considering: when is each of the four realms of provisioning – household, commons, market and state – best suited to delivering humanity’s diverse wants and needs? What changes in technology, culture and social norms might alter that? How can these four realms most effectively work together – such as the market with the commons, the commons with the state, or the state with the household? Likewise, rather than focusing by default on how to increase economic activity, ask how the content and structure of that activity might be shaping society, politics and power. And just how big can the economy become, given Earth’s ecological capacity?

First, rather than narrowly self-interested we are social and reciprocating.

Second, in place of fixed preferences, we have fluid values.

Third, instead of isolated we are interdependent.

Fourth, rather than calculate, we usually approximate. And fifth, far from having dominion over nature, we are deeply embedded in the web of life.

Over the following two centuries, economic theory came to be founded upon the fundamental assumption that competitive self-interest is not only man’s natural state but also his optimal strategy for economic success. the growing use of monetary incentives in policies aimed at ending human deprivation and ecological degradation. Initial evidence suggests that monetary payments often crowd out existing motivations by activating extrinsic rather than intrinsic values. As the case studies described below reveal, there may be far wiser ways – drawing on what we now know about values, nudges, networks and reciprocity – to nurture human nature towards the Doughnut’s safe and just space.

Instead of engaging existing intrinsic commitments, such as pride in cultural heritage, respect for the living world, and trust in the community, some schemes inadvertently serve to erode those very values and replace them with financial motivation.

Using money to motivate people can throw up surprising results, we often don’t understand the complex interplay of human values and motivations well enough to anticipate what will happen, and so that calls for caution.

Becoming Regenerative

Today’s economy is divisive and degenerative by default. Tomorrow’s economy must be distributive and regenerative by design. An economy that is distributive by design is one whose dynamics tend to disperse and circulate value as it is created, rather than concentrating it in ever-fewer hands.

An economy that is regenerative by design is one in which people become full participants in regenerating Earth’s life-giving cycles so that we thrive within planetary boundaries.

Redistribution

Capitalism automatically generates arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities that radically undermine the meritocratic values on which democratic societies are based. Don’t wait for economic growth to reduce inequality – because it won’t. Instead, create an economy that is distributive by design.

Such redistributive policies can be life-changing for those who benefit from them. But they still may not get to the root of economic inequalities, because they focus on redistributing income, not the wealth that generates it.

Tackling inequality at root calls for democratising the ownership of wealth, It is clear that the digital revolution has unleashed an era of collaborative knowledge creation that has the potential to radically decentralise the ownership of wealth. But, it is unlikely to reach its potential without state support.

How can the state start helping the knowledge commons to realise its potential? In five key ways.

First, invest in human ingenuity by teaching social entrepreneurship, problem-solving and collaboration in schools and universities worldwide: such skills will equip the next generation to innovate in open-source networks like no generation before them.

Second, ensure that all publicly funded research becomes public knowledge, by contractually requiring it to be licensed in the knowledge commons, rather than permitting it to be locked away under patents and copyright for private commercial gain.

Third, roll back the excessive reach of corporate intellectual property claims in order to prevent spurious patent and copyright applications from encroaching on the knowledge commons.

Fourth, publicly fund the set-up of community maker-spaces – places where innovators can meet and experiment with shared use of 3D printers and essential tools for hardware construction.

And lastly, encourage the spread of civic organisations – from cooperative societies and student groups to innovation clubs and neighbourhood associations – because their interconnections turn into the very nodes that bring such peer-to-peer networks alive.

Widening such access to the global knowledge commons will be one of the most transformative ways of redistributing wealth this century. Rather than wait (in vain) for growth to deliver greater equality, twenty-first-century economists will design distributive flow into the very structure of economic interactions from the get-go. Instead of focusing on redistributing income alone, they will also seek to redistribute wealth – be it the power to control land, money creation, enterprise, technology or knowledge – and will harness the market, the commons and the state alike to make it happen.

Rather than wait for top-down reform, they will work with bottom-up networks that are already driving a revolution in redistribution. What’s more, they will match this revolution in distributive economic design with an equally powerful one in regenerative economic design, as the following chapter explores. they found that environmental quality is higher where income is more equitably distributed, where more people are literate, and where civil and political rights are better respected.

It’s people power, not economic growth per se, that protects local air and water quality. Likewise it is citizen pressure on governments and companies for more stringent standards, not the mere increase in revenue, that compels industries to switch to cleaner technologies.

Summary

The twenty-first-century task is clear: to create economies that promote human prosperity in a flourishing web of life, so that we can thrive in balance within the Doughnut’s safe and just space. It starts with recognising that every economy – local to global – is embedded within society and within the living world.